Published: 14 December 2025

The longstanding public demand and decades of relentless advocacy by stakeholders, particularly articulated as a key aspiration of the July movement, for an independent police commission, have been ruthlessly and shamelessly shattered by the Police Commission Ordinance 2025, gazetted on December 09, 2025. The ordinance is conceptually and strategically flawed. It sabotages the whole purpose of an independent police commission.

An outfit created based on this ordinance will not only fail to fit the purpose but also further entrench the government's control, especially the home ministry, through the vested forces of administrative and police bureaucracy, over any possibility of police professionalism and accountability. It will at best become a post-retirement resort for deputed and in-service bureaucrats who will deliver the job of protection, promotion and impunity of police wrongdoings that police of Bangladesh are known for. It will serve no public interest while public money will be unnecessarily wasted under the façade of a police commission.

The framers of this ordinance have failed to realise that the indispensable precondition of a police commission, people expect, is that it must first and foremost be independent and free from any influence of the government and police itself to ensure police accountability, transparency, and professionalism by investigating abuse of power, including all forms of disproportionate use of force and corruption without fear or favour. What we have under the ordinance is an opening to legitimise just the opposite. An outfit created through this ordinance cannot operate independently from political, governmental and police influence—especially that of the home ministry, the clutches of civil and uniformed bureaucratic power. It will not be public interest-oriented where the rule of law prevails; police and citizens' grievances and complaints are effectively addressed; police governance meets the standards of transparency and accountability; and public trust in the police is regained.

Independence of the proposed police commission is crucial, not only because our police force has become infamous for being involved unaccountably in all forms and categories of abuses of power, brutality, and crime, but also due to the deep politicisation of the police. Over the years, it has transformed into a weapon for the "winner-takes-all" game, becoming a pillar of authoritarianism for 15 years, enabled by both the home ministry and the police rank and file, who were both victims and beneficiaries. This business model of police force's professional bankruptcy cannot be dismantled overnight, though an unprecedented opportunity for comprehensive police reforms was created at high cost in the wake of the July uprising, at the core of which lies the aspiration for an independent police commission.

The Police Commission Ordinance, 2025, issued by the interim government, is regrettably an outrageous affront to this aspiration. It ridiculed the basic requirement of giving the proposed entity—the police commission—the status of independence. The ordinance described the commission as a so-called statutory body, while there is no mention of the term or concept of independence, nor any provision for it to function outside the control of the law ministry and selected police officials and bureaucrats. It will be formed under the full authority of the government and operated as such, which doesn't make any sense for a commission worth its name.

In para 6, the ordinance dictates that it will be headed by five individuals, of whom one must be a retired bureaucrat and another a retired police officer, who will also be the commission's member-secretary, an unusual provision for any such commission. While both national and international good practices do provide the prerequisites, such as expertise, experience and professional composition of individuals to be represented, there is no example of a priori determination of the specific categories and numbers of individuals to be appointed, and that too with clear conflict of interest. Not only that, while most such commissions typically have a secretary to the commission who works under its supervision, reporting to it and attending meetings ex-officio, non-voting at best, subject to procedures determined by the commission, nowhere is there a provision for a member-secretary. And that too a representative of the police, who, in all likelihood, will be hand-picked by the government—it will be the determining factor making the commission compliant to government dictates.

Furthermore, the ordinance also renders the selection committee a mere rubber-stamp. Para 9 of the ordinance proposed that the selection committee be composed of six members, including the cabinet secretary and home secretary, who will, quite understandably, play the determining role in the proceedings and selection. Additionally, the main opposition party in the parliament does not get to nominate its representative for the selection committee. The ordinance authorises the parliamentary committee on home to carry out that task. Anyone aware of the track record of parliamentary committees would not doubt that this choice would at best be controversial, if not imposed by the ruling party.

Besides, it is not clear why the home ministry has to provide secretarial support to the selection committee and not a separate office so that the scope of conflict of interest can be minimised. Moreover, why should the selection committee recommend two names for appointment against each commission position, instead of one, as in the case of the new National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) Ordinance? The latter provision limits presidential discretion, usually blessed by the ruling party. Also, why should it not be mandatory to disclose the shortlisted names for public information?

The range of items listed under para 13 is also conceptually flawed, lacking a proper understanding of human rights and the role of police. It provides for striking a balance between "public security and human rights," thus failing to ensure precedence of human rights, which by itself is an essential prerequisite of public security. Nevertheless, the term, public security, remains undefined in the ordinance, leaving scope for arbitrary interpretation and abuse. The para also provides the proposed commission with the authority to only recommend measures, with practically no provision for enforcement.

Para 13 also mentions two separate committees—Citizen Complaint Management Committee and Police Grievance Redress Committee—both to be composed of the three commission members. Clearly, their work will be hindered by conflicts of interest due to the influence of bureaucratic and police dominance within the commission, as mentioned earlier. Para 19 (2) authorises the commission to "settle through coordination" any complaint that could be in the jurisdiction of the NHRC, which is another example of a conceptual flaw, because in such instances, NHRC's authority should have precedence.

Finally, the proposed commission under this ordinance will be practically governed, managed and operated by deputed officials from the bureaucracy and police at practically all levels with no financial independence as provided under para 23, 24, and 25.

The key message of the Police Commission Ordinance, 2025, is: forget about police reform in Bangladesh, treat it as an eyewash at best.

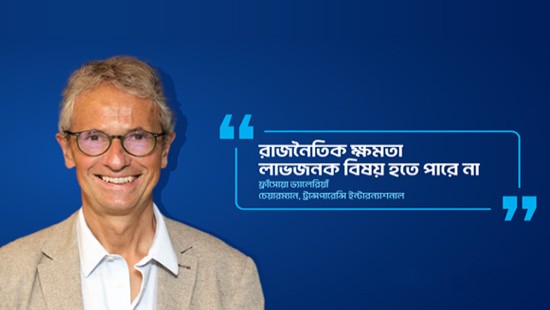

Dr Iftekharuzzaman is executive director of Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB).

The Daily Star

14 December 2025

Link